Sometimes I think of all the times in this sweet life when I must have missed the affection I was being given. A friend calls this “standing knee-deep in the river and dying of thirst.”

– Robert Fulghum

I started packing for a move today. I hate packing, and I hate moving, so it’s a special kind of day when I get to be thinking about both.

The nice moment, though, is the special kind of reflection I forget is part of moving from one home to another. It’s the process of deciding what piece of the past, what belongings in the old house need to make the transition to the new house so that it might be the new home as well.

For me, in every move since I first became a classroom teacher, there is a manilla folder that gives me pause. It is similar to the memory boxes my mom kept for my sister and me as we were growing up.

It’s not labeled, and it’s outgrown what’s inside long ago. Still, a manilla folder is the right container.

If it had a label, it would simply be “The Good Stuff.”

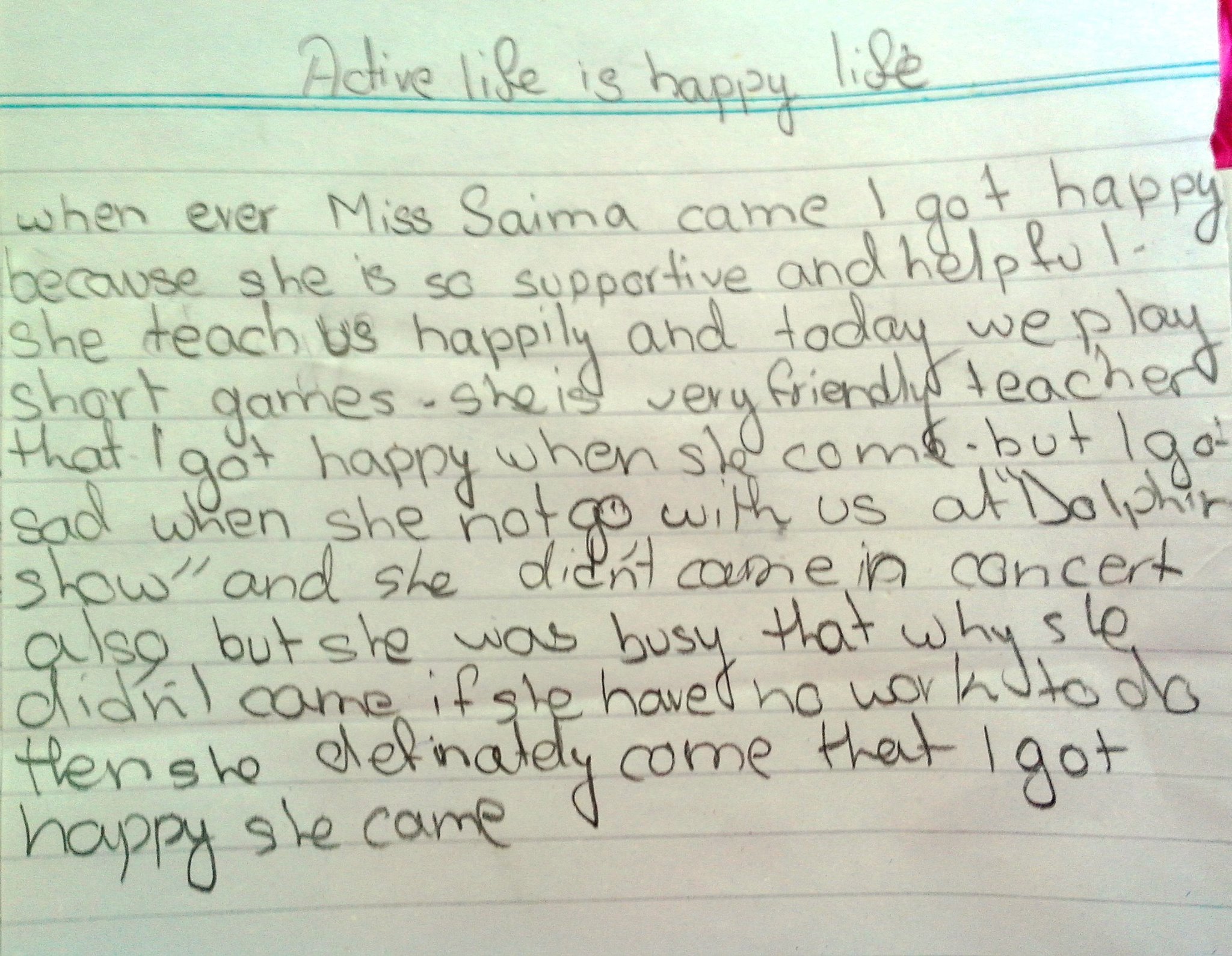

This is a folder that holds the notes and fragments of teaching. There are letters from parents, drawings from students, notes passed in class. These aren’t all the piece of teaching.

The folder doesn’t hold any perfunctory Christmas cards clearly scribbled at the behest of a doting parent.

Instead, there’s the note from Kyle, whom I got to teach when he was in 8th grade. Toward the end of the year, Kyle and I had a handful of talks about how his group of friends was changing. He talked in the most nascent of ways about who he wanted to be in high school and beyond, and I held my tongue as much as I could because I knew he had to learn these lessons for himself.

Kyle’s note, scribbled in the scratch that belied the haste in which it was written is a simple, heartfelt thank you for simply being there and listening. I knew what it meant to me that Kyle was willing to work through his thinking aloud to me. It was this note, though, that let me know Kyle was also grateful for those conversations.

One card is written out in the experienced hand of a mother. I’d been able to teach her son three of his four years in high school. They had not been uneventful. His graduation was of the sort where those faculty in his orbit had looked at one another as he crossed the stage and traded a glance that said, “We made it.”

This mother’s note simply said she knew things had been trying and she was forever grateful for the time and care I’d shown her son.

The thing I remember most when I leaf through my file is that these notes arrived on my desk or in my mailbox as a result of no superhuman effort, no extraordinary circumstances. These came as a result of me doing my job and those most affected by that work taking the time to let me know they took notice and were grateful.

As much as these notes were a place of support at the end of days of teaching where the temptation was to give it all up to be a turnip farmer, they mean something else now. In my work supporting teachers, leaders, and learners, these notes and the things that led them to being are a reminder of the importance of taking time (just a few moments) to thank the people around me for the time and dedication they show when they do the work we do.

I love my file of good stuff. Even more, I love the idea that something I jot down might make its way into someone else’s good stuff.

![Dunlap Broadside [Declaration of Independence]](https://farm4.staticflickr.com/3633/3694394069_2d41fa536e.jpg)