Just before I started my new job last year, I tried to think about what kind of signature I might want to add to conversations. I was about to meet many more teachers in our district than I’d ever had the chance to interact with before, and I wanted to be conscious of the impression I was making – using it to someone start to shift culture.

The question I settled on, “What are you reading?” As a language arts coordinator, it made sense.

When I would meet with grade-level teams, start a professional development workshop, engage in a coaching conversation it was the same question. From k to 12 I’d ask the room, “What are you reading?”

A few days after a meeting with a team of elementary teachers whom I’d worked with several times across the year, their principal told me one of the teachers had confided he was upset following our time together. I was understandably worried. Not only do I take my job to support teachers seriously, I’m a Midwesterner. “No, no,” the principal said, “He thought the conversation and work were great. He was upset because he made sure he had an answer for when you asked what he was reading and then you didn’t ask.”

I hadn’t.

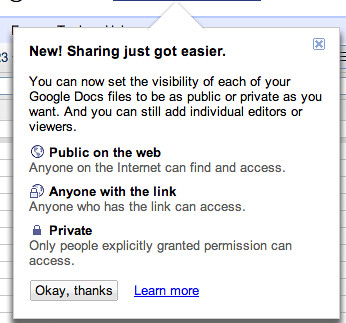

It was the end of the year, I was working with a team of teachers with whom I’d established a rapport, and I hadn’t felt a need to break the ice. What had initially been meant as a seemingly innocuous question that could start to chip away at culture had been repositioned in my mind as a convenient ice breaker. The thing was, this exchange was evidence the culture was changing. The same teacher who was upset I hadn’t asked was one of the many many many teachers throughout the year who had needed to take a beat on my first asking of the question.

“I’m not really a reader,” many teachers would say before we dove into the work of helping students build identities as lifelong readers. To a person, though, they were able to list several texts when I would push, “So you didn’t read anything yesterday?”

“Well, not a book,” they’d say, and I’d point out that I hadn’t asked what book they were reading. From there, teachers would talk about magazines, news sites, blogs, and any other medium you can think of. By the end of the conversation, I’d usually jotted down a few new places I was interested in reading.

Then, I would point out, “If this is the longest conversation you’ve ever had in this building about yourself as a reader, then we’re missing an amazing opportunity to connect with our students.” If the kids in our care only see us as people who make them read the things you’re “supposed” to read in school, and not actual daily readers ourselves, then we’re missing myriad opportunities to be powerful role models of literacy.

After this conversation at one of our middle schools, the school’s librarian polled the faculty on their favorite books and then took pictures of each person holding the book. She pulled the titles from the library shelves and displayed them alongside the pictures at the top of the stacks. Within days, each of the teacher-preferred titles was checked out.

Another teacher of elementary students took to posting a printed photo of the cover of whatever book she was currently reading outside her door. Alongside it was a paragraph explaining what the text was about and another recounting how she had come to choose the book.

One principal posted photos of what she was reading on her office door – a teacher book and a juvenile title. When students found themselves in the office as a result of a poor choice, situations were diffused when conversations started with questions of whether they’d ever heard of either of the titles.

In my own office, where only adults ever come to visit me, I have two printed pictures hanging, the book I’m reading as part of professional learning and the book I’m staying up too late each night reading (Chris Emdin’s For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood and Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses, respectively).

The folks I meet with know me pretty well now or know what I do in the district before we sit down. As a result, I’ve shirked asking the question. I plan to bring it back. I miss the expectation of it. I miss the positive assumption that the people with whom I work, people charged with fostering learning daily, are readers. I also missed the sometimes overwhelming lists of recommendations the question elicited like when I asked the question in a meeting of librarians and we ran dangerously close of scrapping the whole meeting agenda while we shared our newest favorites. You know what, though, we captured every title and everyone in the room asked if we would share the list in the meeting notes. Building an expectation of reading means building a culture of reading. And that means giving people space to talk about their reading.

What are you reading?

I struggle mightily every day not to scream, “Stop making everyone read the same damned book!”

I struggle mightily every day not to scream, “Stop making everyone read the same damned book!” As is so often the case,

As is so often the case,  I’ve been thinking about the things I tell people about myself. I tell them I’m an educator, I tell them I’m a writer, I tell them I’m a vegetarian. I’m imagining, you do something similar. There are labels you carry with you and offer up to new people when you meet them. They might also be labels you count on as the fascia that binds you to your network of friends and colleagues. I wonder, though, if your labels are anything like mine.

I’ve been thinking about the things I tell people about myself. I tell them I’m an educator, I tell them I’m a writer, I tell them I’m a vegetarian. I’m imagining, you do something similar. There are labels you carry with you and offer up to new people when you meet them. They might also be labels you count on as the fascia that binds you to your network of friends and colleagues. I wonder, though, if your labels are anything like mine.