Had a meeting with a middle school teacher today. He and his team were asking for a specific app to be moved into our self service directory for their middle school students. The app proports to help students develop their vocabulary skills, so it got funneled to me in the chain of command.

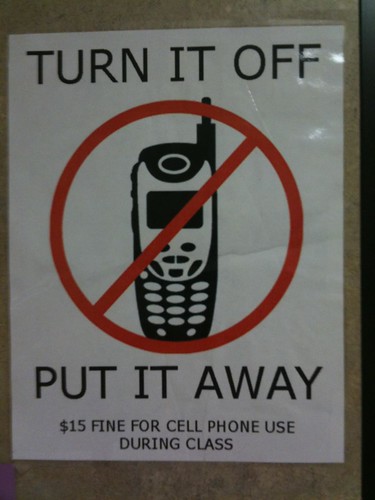

To be honest, this app has been a thorn in my side since I started the job. It’s not horrible, but it’s not great. When I’d been forwarded the initial request, I’d responded that I was pretty sure it was already in self service and, for what it’s worth, that I was reticent to recommend students using any app during class time which took away from real reading and writing.

It turned out, I was wrong.

It turned out, I was wrong. Not about the reading and writing, but about the app already being in self service. The last time I had this conversation, we were able to allow apps to be accessible at a school level. Now, we are not. This meant I would be approving access not just for one school, but for all middle schools.

What I’d considered as one kettle of fish had turned into a whole other of said kettles.

Thus, the meeting with the teacher. We started with him suggesting I talk through my thoughts on the app and then he’d fill in with his team’s plan. I laid out my concerns and he said, “Yes, we think exactly the same thing.” Then, he explained the team only wanted the app so students had something to use outside of class to think through vocabulary. Remember, it’s not horrible, and in the face of so many possible app which are horrible, the team was attempting to stem the tide of horrible.

“I mean, we’re professionals.”

“We want them to be doing real reading and writing as much as possible too,” he said, “I mean, we’re professionals.”

He didn’t say it defensively or as a form of semantic brinksmanship. He simply mentioned he and his team’s professionalism as a reason they too would not want their students using this app during class time or as a way to supplant real reading and writing.

I told him I understood exactly and had assumed as much. I then explained how our infrastructure had changed, shifting their ask from one of a single school to one of all middle schools. “Oh…” he said, “I understand.”

I explained that I had to consider inclusion of the app as possibly being interpreted as at least a tacit endorsement – something that particularly worried me when considering novice teachers who might be looking for anything to get them through their first few years. I went on to explain I’d approved the inclusion of the app and I’d be writing and sharing a blog post from the department blog outlining guidance and my reservations for other middle school teachers in the district.

He had told me early in the conversation that this app wasn’t a hill he was interested in dying on, and my explanation was meant as a signal the same was true for me.

I wish it didn’t strike me as so odd how civil and respectful our entire conversation was. Since taking a role in district leadership, my default expectation for the tenor of such conversations has shifted to one of combativeness. I work “downtown” after all or I’m from “the district” or “central office.”

I wonder if this teacher entered into the conversation with the same sort of expectations. Did he think I was going to issue a summary judgement or simply pretend to listen to his concerns and then make the same decision I’d planned on when starting the meeting? Perhaps.

That makes me a bit downhearted. When I talk to folks about what I do, I have and always will explain my job is to support students and teachers. I can only be successful at helping all of our students become fully literate citizens if I can also support all of the adults in our system get the learning and resources they need.

Understanding all of those needs means having as many conversations as possible like the one I had today.