A few days ago, for a moment of levity before a more principled discussion, we watched the video below in one of my seminars.

How do you say what your kids say?

A few weeks ago, I was observing a student teacher. In our debrief, I said, “When you’re asking students for answers, you put those answers into your own words much of the time. What might that say to the students?”

We then had a conversation about the possible implication that changing the students’ words could be perceived as correcting them – that what they were saying wasn’t good enough to be repeated as stated or written on the board verbatim during class notes.

My thinking has been that such switching of language could lead to decreased participation from students:

When I speak, she changes my words. This must mean that my answers are wrong. I should stop speaking so I don’t sound stupid.

I challenged the student teacher to make an effort to repeat answers as given and start writing them on the board verbatim.

As I read the second essay in Eleanor Duckworth’s “The Having of Wonderful Ideas” and Other Essays on Teaching and Learning. I’m starting to question this thinking. Discussing the work of one linguist, Duckworth writes:

If the children were asked to repeat a sentence of a form that did not correspond to their grammar (for instance, “I asked Alvin whether he knows how to play basketball”), they repeated the sentence, but with their own grammar (“I asked Alvin do he know how to play basketball”). It was not the words they retained, it was the sense. Then the sense was translated back into words, words that said the same thing but were not the same words.

That sound you might be hearing is my brain bubbling with questions:

- If we accept that children’s retention of meaning, but discarding of words is a valid communication of meaning, does the same hold true for teacher’s repetition of children’s words?

- Given the power structure of the classroom, does the teacher’s re-phrasing of a student’s response mean something different (or negative) than a student’s re-phrasing?

- When do we decided re-phrasing student responses is teaching and when do we decide not to in favor of letting students know they’re free to share and expand on ideas?

I don’t have answers here, and would definitely benefit from hearing how other people think about how they accept student answers.

What does this look like in your practice?

Thoughts on “The Having of Wonderful Ideas”

Outside of the general curriculum of my doc program, I’m trying to pick up other texts from time to time. One of those texts has been “The Having of Wonderful Ideas” and Other Essays on Teaching and Learning by Eleanor Duckworth.

Duckworth, a professor at HGSE and student of Jean Piaget, retired from professing at the end of last year. I missed taking her class and continue to kick myself.

Before I get into the book, a moment of the evidence of the kind of character Duckworth possesses. Standing in line last year for the Harvard-wide commencement ceremony, my friend and I were joined by Duckworth dressed in full doctoral regalia. She told us she’d never walked with students before and figured this would be her last chance. She stood in the sun with us as we waited to file in and sat amongst us during the ceremony. To my knowledge, she was the only faculty member to do so and was driven simply by curiosity.

“The Having of Wonderful Ideas” opens the book and presents several key ideas for how people can approach teaching other people. Not the least of these is Duckworth’s statement, “The having of wonderful ideas is what I consider the essence of intellectual development.” I can’t imagine a better stated purpose for teaching and learning.

Below are some key points:

He was at a point where a certain experience fit into certain thoughts and took him a step forward…The point has two aspects: First, the right question at the right time can move children to peaks in their thinking that result in significant steps forward and real intellectual excitement; and, second, although it is almost impossible for an adult to know exactly the right time to ask a specific question of a specific child–especially for a teacher who is concerned with 30 or more children–children can raise the right question for themselves if the setting is right. Once the right question is raised, they are moved to tax themselves to the fullest to find an answer.

It’s a dangerous notion not all teachers are willing to adopt – that children might be able to ask the right questions or that teachers might not know the right questions.

Duckworth has some guidance for the creation of “the right time” for the development of these questions:

There are two aspects to providing occasions for wonderful ideas. One is being willing to accept children’s ideas. The other is providing a setting that suggests wonderful ideas to children–different idas to different children–as they are caught up in intellectual problems that are real to them.

and

When children are afforded the occasions to be intellectually creative–by being offered matter to be concerned about intellectually and by having their ideas accepted–then not only do they learn about the world, but as a happy side effect their general intellectual ability is stimulated as well.

and

If a person has some knowledge at his disposal, he can try to make sense of new experiences and new information related to it. He fits it into what he has. By knowledge I do not mean verbal summaries of somebody’s else’s knowledge.

The key sentiment here and throughout the text is listening to children – listening to their thinking, their questions, and the manners by which they work to answer their questions.

Doing this requires a relinquishment of the notion that all children should be doing and learning the same things at the same times based on their born-on date. It’s a tough idea to relinquish and an easy one to cling to when standards, textbooks and curricula are all built to suggest chronology, not development, should decide rule the day-by-day learning.

It’s not impossible to create such spaces in district with more stringent requirements. Subversion of the system need not mean destroying it. Much can be accomplished through co-opting language. If Duckworth is correct, the right questions will arise. If curricula are correct, the standards will be uncovered by the naturally-occurring questions.

Listening (to understand) is necessary.

For more on Duckworth, watch her HGSE commencement speech below or head to Constructing Modern Knowledge 2013 in NH July 9-12.

Watch Now: Bill Moyers & Co. “United States of ALEC”

At first I was thrilled when I saw a journalist of Bill Moyers’s standing reporting in-depth on ALEC.

Then, I realized the demo draw of Bill Moyers & Company and got a bit disheartened. Luckily, there’s the Internet.

Watch this. Then, share it.

Some thoughts on re-mediation in the teaching of literacy

For one of my grad courses, I signed up to read and start discussion on the class blog about the article “A Socio-Historical Approach to Re-Mediation” by Mike Cole and Peg Griffin. Catchy title, right?

The blog is walled off, but I was so taken with Cole and Griffin’s ideas, that I’m reposting my post here.

Some things that caught my attention:

…Cole, Griffin and I get into a disagreement here. Then, I reminded myself they were writing in 1978, so the kind of computer re-mediation they were talking about had more to do with the basics of phonetic, piece-meal instruction than with what current computers are able to do.

Still, if you look at computer use in literacy instruction in most classrooms, you’ll find pre-packaged software that is simply an electronic version of the instruction Cole and Griffin describe.

…Yes, let’s do this…more.

The Questions

Learning Grounds Ep. 007: In which Bud Hunt and Zac talk maker spaces, community, and grilled cheese

In this episode, Zac sits down with Bud Hunt for our first-ever pubcast, and the two discuss the need for maker spaces, teacher agency, and the building of the two.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

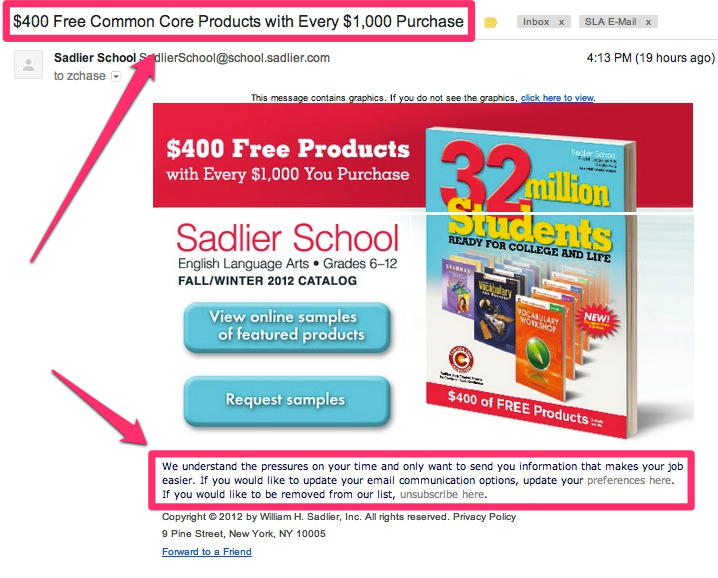

So long as Common Core is about students, learning and America; I guess that’s okay

We Should Embrace Confusion

The video below, from Yes to the Mess author Frank Barrett, touches on the idea of disruption of routine as a catalyst to innovation, that wimpiest of buzzwords.

Still, if your goal is to get folks – let’s say teachers and students – thinking differently and creatively about their learning, it’s an interesting line of thinking. More important than Barrett’s point about disruption, though, is the point he (mostly indirectly) makes about the role of confusion in helping people think differently.

It connected nicely with a passage from John Holt’s How Children Learn, which I’d re-visited for class this past week:

Bill Hull once said to me, “If we taught children to speak, they’d never learn.” I thought at first he was joking. By now I realize that it was a very important truth. Suppose we decided that we had to “teach” children to speak. How would we go about it? First, some committee of experts would analyze speech and break it down into a number of separate “speech skills.” We would probably say that, since speech is made up of sounds, a child must be taught to make all the sounds of his language before he can be taught to speak the language itself. Doubtless we would list these sounds, easiest and commonest ones first, harder and rarer ones next. Then we would begin to teach infants these sounds, working our way down the list. Perhaps, in order not to “confuse” the child-“con- fuse” is an evil word to many educators-we would not let the child hear much ordinary speech, but would only expose him to the sounds we were trying to teach. (emphasis mine)

John Holt. How Children Learn (Classics in Child Development) (p. 84). Kindle Edition.

Perhaps we’re getting less and less out of teachers and students (and I’m not convinced that we are) because the systems in which they operate are working at top speed to make certain they avoid confusion at all levels. Teaching scripts, standardized test instructions, online learning platforms, google search – all are designed in ways that make it as difficult as possible to be confused.

If a teacher working from a pre-packaged lesson plan never has to wrestle with how to solve the problems of student engagement or differentiated instruction because the introductory set is included and the lesson’s been pre-leveled, there’s very little thinking to be done. If I’m not confused, I’m not likely be solving problems.

Similarly, if the directions to an assignment spend a few paragraphs explaining what information I should include in the heading, how many sentences constitute a paragraph, what I should include in each of said paragraphs, and the topics from which I’m allowed to choose, it’s unlikely I’ll risk the type of thinking that could perplex or confuse me as to what my exact position regarding my topic might be.

To be certain, obtuseness that renders teaching and learning inaccessible is not helpful. At the same time, clarity that renders the two unnecessary is harmful.

To Innovate, Disrupt Your Routine – Video – Harvard Business Review.

The IRL Fetish – The New Inquiry

Twitter lips and Instagram eyes: Social media is part of ourselves; the Facebook source code becomes our own code…

Many of us, indeed, have always been quite happy to occasionally log off and appreciate stretches of boredom or ponder printed books — even though books themselves were regarded as a deleterious distraction as they became more prevalent. But our immense self-satisfaction in disconnection is new. How proud of ourselves we are for fighting against the long reach of mobile and social technologies! One of our new hobbies is patting ourselves on the back by demonstrating how much we don’t go on Facebook. People boast about not having a profile. We have started to congratulate ourselves for keeping our phones in our pockets and fetishizing the offline as something more real to be nostalgic for. While the offline is said to be increasingly difficult to access, it is simultaneously easily obtained — if, of course, you are the “right” type of person.

No need to raise your seat back: What happens when teachers lose sight of the destination

The man sits asleep, mouth agape in his window seat as the flight attendant stops by and gingerly taps him on the shoulder.

“Sir,” says the flight attendant, “We’ll be landing soon, and I need you to put your seat up.”

“I can’t,” says the passenger, “Whenever I try, it just falls back down. I think it’s broken.”

“You need to press the button,” says the flight attendant.

“I did. It just keeps falling.” He demonstrates.

“Well, can you put up the seat beside you,” says the flight attendant as he walks away.

The passenger is suggesting someone might want to report the broken seat, but the flight attendant has already moved on.

The entire scene is reminiscent of many teachers’ approach to students and what they have decided are the correct behaviors.

Anyone who has ever traveled by air knows the vehemence with which flight attendants insist passengers put their seat backs and tray tables in the full upright position.

So too might anyone who observes an American classroom note the force with which many teachers insist students follow exacting classroom procedures and practices. Students must submit their homework at a given time, tests must be completed within a certain interval, essays must be formatted according to set parameters. In many cases, if any of these standards is not met, the work will not be accepted. The students will not be cleared for landing.

Teachers are tripping over procedures with little regard to their intended destinations.

Certainly, it is important for a student to learn the lesson of submitting work in a timely manner. At the same time the tardiness of work should not mean a student’s effort up to that point be disregarded.

Why, then, do many teachers impose such draconian measures in their classrooms? They do it for the same reasons many flight attendants insist on upright seats, not because it is imperative for the landing of the plane, but because it is one of the few things still within their control.

If teaching is entirely dependent on others listening and observing instruction and then internalizing it, there is little wonder teachers might savor any element of control they can find when faced with limp success rate of much traditional teaching.

One option, the option of which we are loud proponents, is to keep the intended destination in mind when responding to the idiosyncracies of student behaviors and accepting successes while working to improve upon failures. This is not easy.

Our flight attendant, too, struggled with keeping the destination in mind. If seat back position is important to the operation of the plane, he would have done well to listen to the passenger and report the defunct chair. Ignoring it now means he and subsequent flight attendants will wage constant battle with that seat when a few moments of focused attention could save mountains of frustration.

Teachers too could learn from this piece of the story. Punishing the student who has formatted his essay incorrectly without taking the time to help the student develop a plan for avoiding the error in the future only insures headaches down the road.

Failing to appreciate the work that’s been done while simultaneously punishing the annoyance without working toward a solution leads to something educators are particularly adept at – admiring the problem.