“Harry — I think I’ve just understood something! I’ve got to go to the library!”

And she sprinted away, up the stairs.

“What does she understand?” said Harry distractedly, still looking around, trying to tell where the voice had come from.

“Loads more than I do,” said Ron, shaking his head.

“But why’s she got to go to the library?”

“Because that’s what Hermione does,” said Ron, shrugging. “When in doubt, go to the library.”

― J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

If we are to truly have conversations about students as publishers and have them consider copyright and what rights they want on the works they create, then there are other questions of infrastructure.

The main question, where can we put these things so that they will live on? Sometimes we think that they will be okay if they are put “online” as though the world is standing at their browsers waiting for a new student-produced video to watch.

It is not that we do not value student-produced content on the whole, but that we do not go seeking the fifth-grade research report about bees from four states or two districts away.

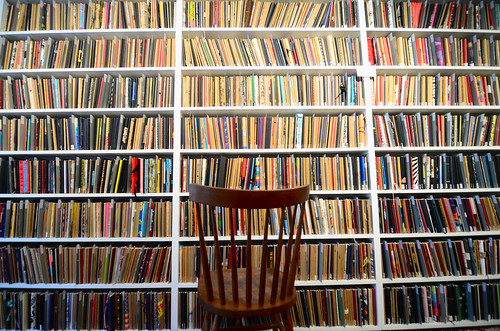

We have places for these things and the chance to imbue them with greater worth and an audience relevant to the places in which they were created – libraries.

One of the first questions I ask of potential digital content management systems is, “Can we catalog and feature student work in your system?” If not, move along.

As teachers increase the number of authentic learning experiences to which they introduce students, it’s going to be important that we not only capture that learning and reflection, but that we have a way of sharing it and cataloging it as well.

I work with middle and elementary schools where the younger students feed directly from the lower school to the upper school. As I work with teachers, I ask how their students are building resources and content for those who will come next.

This is obvious in Language Arts classrooms where students can write stories and create picture books for their elementary counterparts to be logged in the catalog systems of each school and accessible to students.

Less obvious might be the science report, the biography of locally-relevant historical figures, histories of businesses or farms within the city or town.

One of my favorite components of Howard Gardner’s definition of intelligence is the ability to create something of use or value to the culture to which a person belongs. Imagine a library with limited budget that can be stocked by the creations of students. Imagine the one student who has been tinkering on a novel or novella secretly who is given the chance to showcase his work across his school or an entire district.

If, as I’ve argued we ask students to consider how they want to copyright work they’ve released into the wild, then we should also create wild spaces where those works can graze and circulate widely.