33: What have you developed a pavlovian response to? #lifewidelearning16 @MrChase

— Ben Wilkoff (@bhwilkoff) February 2, 2016

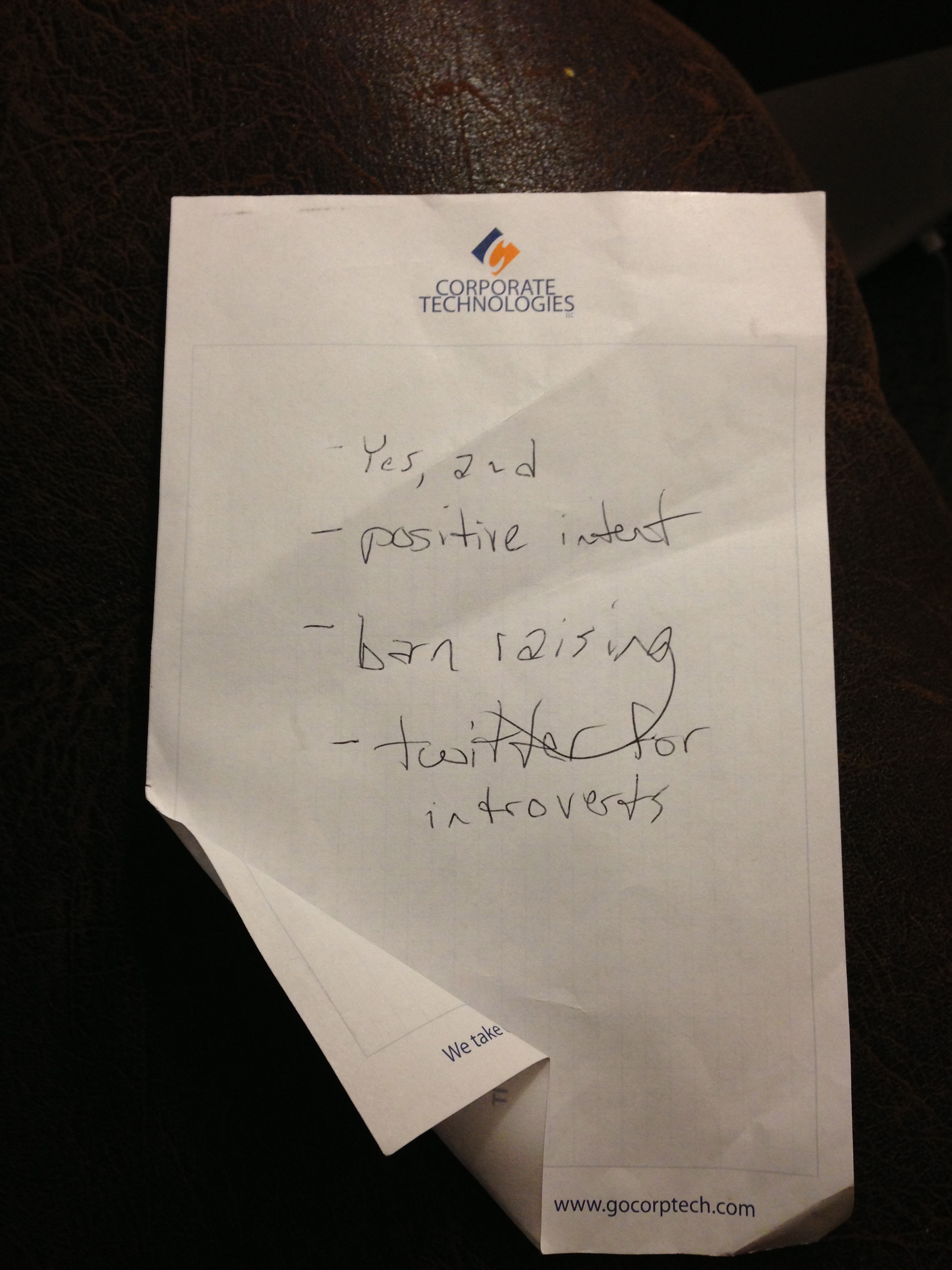

One of the first rules of improv – the most important rule of improv – is to embody a sense of “Yes, and…” Chris and I wrote about it in our book, and this post served as the early draft of that chapter. Sit in a conversation with me for any decent span of time, and you’ll hear me say it. Sit a little longer, and you’ll hear me say it again. I can’t stop myself.

What you won’t know is how often I hear it in my head while I listen to others speak. A colleague in a brainstorming session in the office may respond to someone else’s idea, “Yes that’s a possibility, but here’s why it won’t work…” My brain, fills in the but with an and and begins to imagine where that brainstorm could have gone. It also wonders how the person with that initial idea heard the response. Did she hear what linguists say is actually happening when a but is deployed and process the response as actually not agreeing with her idea?

My Pavlovian response to the little buts sometimes gets me in trouble when I’m faced with a big but. A few weeks ago, when editing a piece of writing from a colleague, I went on a replacing rampage and suggested the removal of every but he’d used throughout the draft. Having satisfied my compulsion, I sent the draft back.

A day later, the next draft arrived in my inbox. All of the little but-to-and revisions had been accepted. Midway through the piece, a comment, “These ideas don’t go together. If I use and here, people are going to think I support the bad policy I mention first, and the more appropriate policy I pose after the but.” He was right. In my flurry of ands, I’d obsessed with form and ignored function.

The answer is moderation. Each of the other edits I’d made set a tone of unity of ideas. The new ands pulled concepts together and tore at false dichotomies. That last but, the one that stayed, wasn’t little. It was deployed to draw attention to why a common misconception needn’t be so in readers’ minds.

This is the danger of Pavlovian responses. We hear the bell ring, but nothing is in the dog bowl. In my instance, I’d become so accustomed to the frequent mindless use of language that I began mindlessly dismissing what they were saying. Not everything is a little but. Some buts are big and necessary. As is the case with so many words, when used without thought, buts used without thought can also start to be buts used without meaning.

This post is part of a daily conversation between Ben Wilkoff and me. Each day Ben and I post a question to each other and then respond to one another. You can follow the questions and respond via Twitter at #LifeWideLearning16.