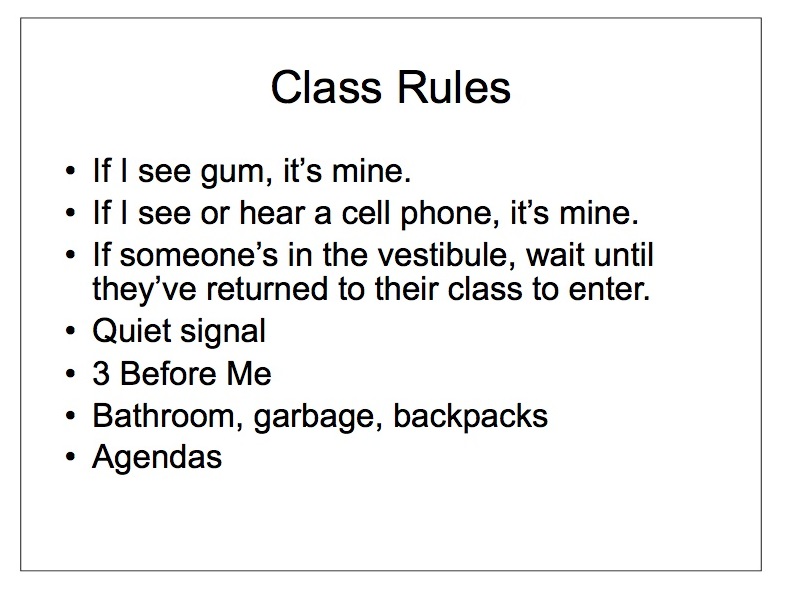

In cleaning out my box.net contents I found a folder containing my slidedecks from the first day of school of my fourth year of teaching. All was well and good until I found the class rules slide below.

Who wrote those two rules? When was I Severus Snape? The thing is, I had a decent idea what I was doing when I made this slide. I’d been in the classroom 3 years and came out of a decent teacher prep experience. The kids I’d taught the year before had taken the school from 47 to 81 percent passing the state writing exam. I had strong relationships with my colleagues, kids and their families. I’d headed up a partner student screenwriting program between our school and the local film festival.

Yet, there I was declaring war on cell phones and gum as though it somehow secured my power as teacher overlord.

Not only that, these were the first two rules I posted. Somehow gum chewing and the sight of a cell phone presented clear and present danger in relation to learning.

This list shows me what I told my students I valued on that first day of school, and it reminds me of how much what I said I believed stood in contrast with the beliefs I enacted as a teacher.

We do that, we get better at what we do, at being people with kids. If I had to guess, I’d say this authoritarian stance was a remnant of teaching students who were quite close to me in age and appearance. It was a stab at drawing a line between who I was and who they were. While I needed that line then, in the years that followed, I worked hard to erase it. I realized the way to teach was to connect, to become a person who mattered that asked students to do work that mattered.

It was a difficult lesson.

One I’m still learning. I’m grateful to younger me for sticking this slidedeck in the cloud time capsule to remind me how I’ve grown.