From Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities:

The more common choice in cities, where people are faced with the choice of sharing much or nothing, is nothing. In city areas that lack a natural and casual public life, it is common for residents to isolate themselves from each other to a fantastic degree. If mere contact with your neighbors threatens to entangle you in their private lives, or entangle them in yours, and if you cannot be so careful who your neighbors are as self-selected upper-middle-class people can be, the logical solution is absolutely to avoid friendliness or casual offers of help. Better to stay thoroughly distant. As a practical result, the ordinary public jobs – like keeping children in hand – for which people must take a little personal initiative, or those for which they must band together in limited common purpose, go undone. The abysses this opens up can be almost unbelievable.

As is, I’m sure, not surprising, I’ve been reading Jacobs through the lens of education and schooling. This lens lends itself nicely to seeing the city as a metaphor for the life of thoroughfares of schools – hallways, restrooms, cafeterias, common areas.

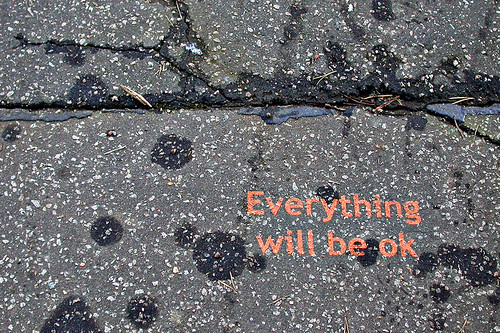

To engender the cultures and climates of healthy, sustainable, supportive schools, we must strike the right balance of public and private. Students should know they are seen, but not feel they are watched or expected to share all the details of what they are doing outside of the day-to-day of schools.

It reminds me of growing up in a small town. My friends and I knew that our teachers knew and saw our parents. We also knew that there was a margin of freedom we were afforded for experimentation into who we were becoming.

The schools we need, like the cities we want, find that balance of private and public and let members of their communities play in all the spaces.

What does this look like? How do we get started?