No matter the class size – from 5 to 50 – every teacher knows the experience of walking out of the building at the end of the day and thinking, “They were out to get me today.” For some, this happens more frequently than others. For some, it happens daily.

Somewhere in the teaching of children, the relationship sours, and teachers lose track of the fact that they teach individuals, growing, young individuals whose emotions and their ability to process those emotions are not fully formed.

Forgetting this key fact about the development of children can lead to another lapse of memory – that of professional perspective. This is the perspective that comes with our ability to stand back and recognize that no child is out to get us, that none of the thousand tiny frustrations throughout our days was set in motion by students’ willful intent to ruin our days.

This must be remembered if teaching is to be a sustaining profession which retains its members through the years.

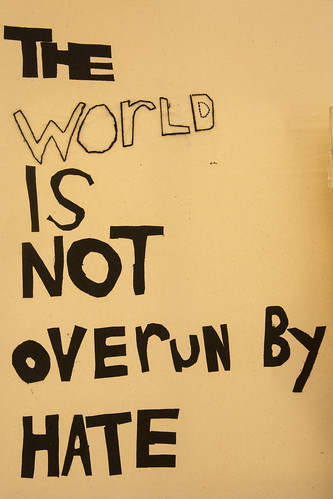

To build the schools we need, we must do more than remember students are not out to get us, we must assume positive intent.

Writing in 2008 for CNNMoney, Pepsico CEO Indra Nooyi described the benefits of assuming positive intent, “Your emotional quotient goes up because you are no longer almost random in your response. You don’t get defensive. You don’t scream. You are trying to understand and listen because at your basic core you are saying, ‘Maybe they are saying something to me that I’m not hearing.'”

Assuming positive intent in our students opens the door for us to seek to truly understand those forces driving those actions and words we would otherwise find frustrating rather than yelling at, punishing, and alienating students.

Assuming a positive intent does not equal assuming that all students enter our classrooms and schools with the intent of learning something new or reaching some new level of academic achievement that day. Depending on circumstances, the intent may be, “I want to keep myself safe and protected.” When students lack the socio-emotional capacity to say these things, their actions may present themselves as lashing out and degrading those around them. Assuming negative intent in these moments only leads us to compounding the problem and fosters a self-fulfilling prophecy that students may find unavoidable.

Assuming positive intent in these moments, asking ourselves what students may be attempting to accomplish through their actions can help us to bring the processing and reflective tools to the table that a student may be lacking in his communication. Sometimes, the most powerful tool is time and space away from the perceived problem.

Whatever the needs, assuming positive intent also builds a self-fulfilling prophecy that can lead students to new ways of meeting their needs that they had not known or considered possible before.

Assuming positive intent in students can be difficult. In a system that does not always build up its teachers or recognize them as professionals, there is almost a conditioning of thought that can drive teachers to assume negative intent to avoid the psychological wounds they may have suffered at the hands of the system.

To assume negative intent, though, is to further that system, to take a defensive stance that says, “I am not going to let you beat me,” when the more disruptive and proactive stance of, “I am going to listen and give you the help you need.”