Last week, Diana sent me a link to this thoughtful piece by Theresa Walter. Writing for the Human Restoration Project, Walter asks, “Does assessment stymie curiosity?”

Citing Susan Engel, Alfie Kohn, and Piaget; Walter navigates the tension between educators’ need to plan and provide structure vs. the natural exploratory curiosity learners can exhibit as they start to dig in and mess about.

In her penultimate graf, Walter writes:

All of this is not to say that classrooms with mayhem at the helm are what I propose — but what I am proposing is that we place curiosity at the center of our instruction. We must ask ourselves to differentiate between producing work and demonstrating growth and learning. I can spend hours writing the answers to someone’s questions, but how does that demonstrate that I have learned? Have I been asked to create my own questions? Have I been asked to look beyond the text and the ideas contained within in order to make connections of my own design? Piaget tells us that students expand their intellectual repertoire when they encounter something that challenges the way they believe the world works. Am I offering those spaces in my instruction?

This is where I want her to keep going, to dig more deeply, and to pull apart the issue further. Structure vs chaos is a false dichotomy. Eleanor Duckworth gave me the idea of messing about as key to learning. My time with design thinking gave me an understanding of the “banks of the river.” In her poem “River Banks, Carolyn Follett writes:

Banks are what hold it a river, give

direction, keep it mitering downward.

Without banks, river loses its way,

becomes a swamp and stills.

All my life I have chafed at river banks,

fighting to spread my currents

in whatever turn needed exploring.

The high song of freedom seemed

to be a music of ‘no banks’,

and yet the whole joy of rivers is pushing,

etching the banks to join the flow,

but having them hold.

Planning a learning experience and fostering student curiosity are not in opposition, but they are the difficult and worthwhile work. We craft the learning experiences as Dewey’s “more mature learners” because (hopefully) we remember the joy of discovering some truth or talent as we did the learning in our own time.

The classroom Engel observes within Walter’s piece is one that clearly allowed for curiosity. We know because children became curious. The specific work here is in being able to realize the assessment was tuned in to the wrong things. I think of my own practice and the realization every student’s product need not be the same. “Choose the form this product takes to best fit the content,” several rubrics/project descriptions asked students.

A moment, too, to think about Kohn’s analogy.

Learning to walk and learning a mathematical concept or how to change the oil in a car are different acts. One is natural and the others are not. The body has evolved to learn to walk. It is a milestone in development. The same is not true of exponents or oil changes. But they both represent constructs of varying value within different social settings. They are constructs some cultures see value in, but our brains do not automatically register that value. They may not even be curious.

In a culture where these things are valued, and perhaps even necessary, it falls upon a teacher to design experiences that attempt to foster that curiosity.

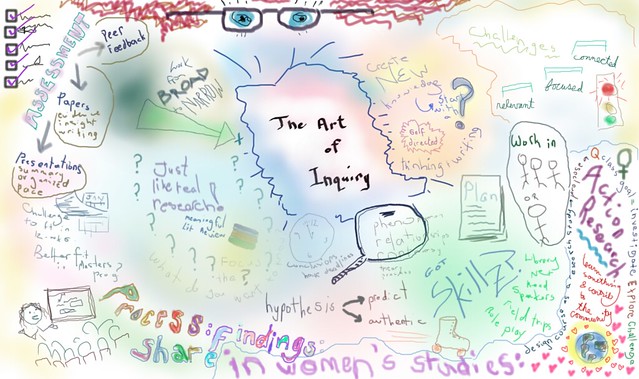

The meat of the conversation, and where I wish Walker had continued, is in the struggle and joy of perfecting the alchemy of helping kids embrace their curiosity while we serve as the more mature learner in the room and providing banks to the river of that curiosity.

As is so often the case,

As is so often the case,