It’s the part of any workshop, presentation, keynote, etc. that starts teachers hesitating. I usually say something like, “Before we begin our work together, let’s make sure we’re here together.”

Then, we do something many of them haven’t been asked to do since, maybe high school – we journal. We write our way in to the work.

Whether it takes place here in the states or with a group of teachers in Capetown, South Africa or Lahore, Pakistan, there is always a moment of hesitation as they settle in.

“Really?” their faces say, “This is how we’re learning about X?”

The answer is yes, it is. Writing and reflecting at the moment of commencement centers participants on where they are, where they’er coming from and where they want to be.

In a recent week-long workshop on project-based learning and educational technologies, I asked participants to journal at the top of each day. The hesitation was there one moment, and a few sentences later, it was gone.

I used the same format I used with high school and middle school students. Projected on the screen at the front of the room were three options: Free write, respond to a given quotation, respond to a given image.

Some days I asked if they’d like to share, other days I did not. While there’s value in the sharing of what teachers write, it’s not the point. They are their own audience in the composition of these reflections. This is a practice meant to help them center.

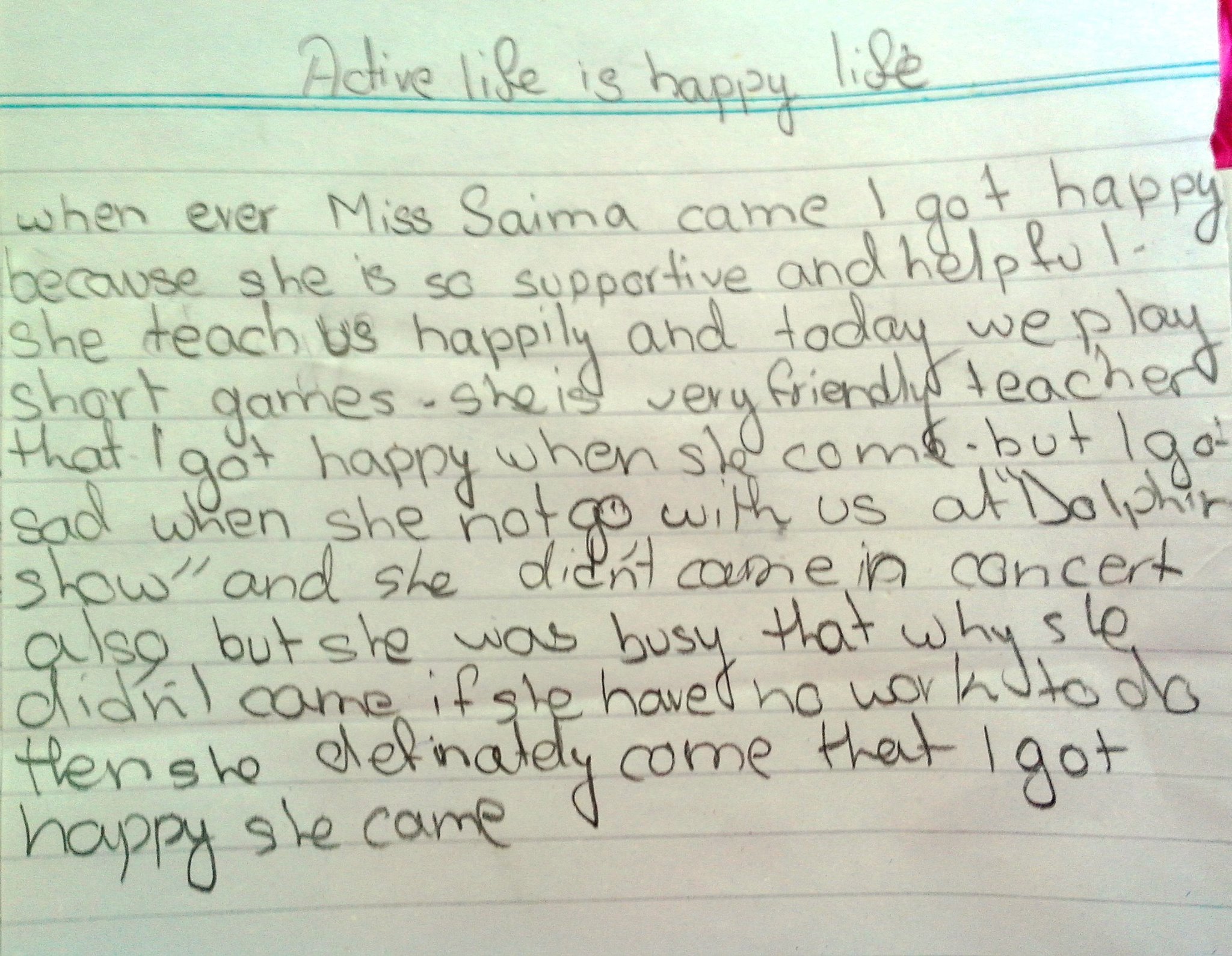

At the end of the week in Pakistan, teachers of all levels and disciplines approached me on breaks telling me they’d enjoyed the journaling and would be taking it back with them to their own classrooms. A few days after I returned to the States, the photo above appeared in my Facebook timeline. Somewhere in the string of 30+ comments, someone asked of the writing, “You don’t teach English do you?”

It was a gentle jibe at the teacher, commenting on the syntactical and grammatical errors in the writing, the postin teacher’s response was perfect, “No, I’m teaching them social studies. I purposely did not do correction as this was journaling for the felf and I committed to students that it’s their piece of writing.”

And there’s the key. With the championing of failure, we must also champion reflective thought. Failure is only worth as much as you learn from it. And, you’re not likely to learn much without pausing to reflect.

Aside from the professing of their own thinking, this type of reflection also frames writing as a different activity than teachers and students might find familiar. Much, if not all, of the writing both teachers and students are asked to do is meant for evaluation, consideration, and judgement of others. A teacher’s lesson or unit plan, a proposal for a field trip, a book report – they are all meant for someone else to read and evaluate the thinking and learning of the write.

Journaling in this way asks the writer, “What makes the most sense for you to be putting down on the page or the screen in this moment? What have you brought with you into this process?” and then gives space for that creation and reflection.

This is all to say, stop, write, reflect, move on.

From Theory to Practice:

- The next time you lead a meeting of other folks (children or adults) ask everyone in the room to write their ways into the day. Take 5-10 minutes and ask people to write about where they’re coming from and what they hope out of their time together.

- Build it as a practice around any major work. For students, ask them to write a reflection on their learning at the end of a lesson, unit, class period, etc. For teachers, take 5 minutes at the beginning or end of the day to reflect on the learning that’s happened and that you hope will happen.

- Respect the privacy of reflection and allow for the choice of taking it to the public forum. If I know you won’t make me share what I write, I’m likely to write more openly and truthfully. I’m also more likely to write something I’m proud of and want to share.