My son was closing the medicine cabinet, toothbrush in hand, and smeared toothpaste all over the mirror. He then tried to wash it off by splashing water from the faucet to the mirror. This did not help.

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” he told me as I walked into the bathroom.

“He got toothpaste all over the mirror, then he got water on the mirror, then he started to smear it all over the mirror, then he got it in my sink. Everything he’s doing is making it worse,” his sister said in the tone of voice reserved for older siblings exasperated at their younger siblings.

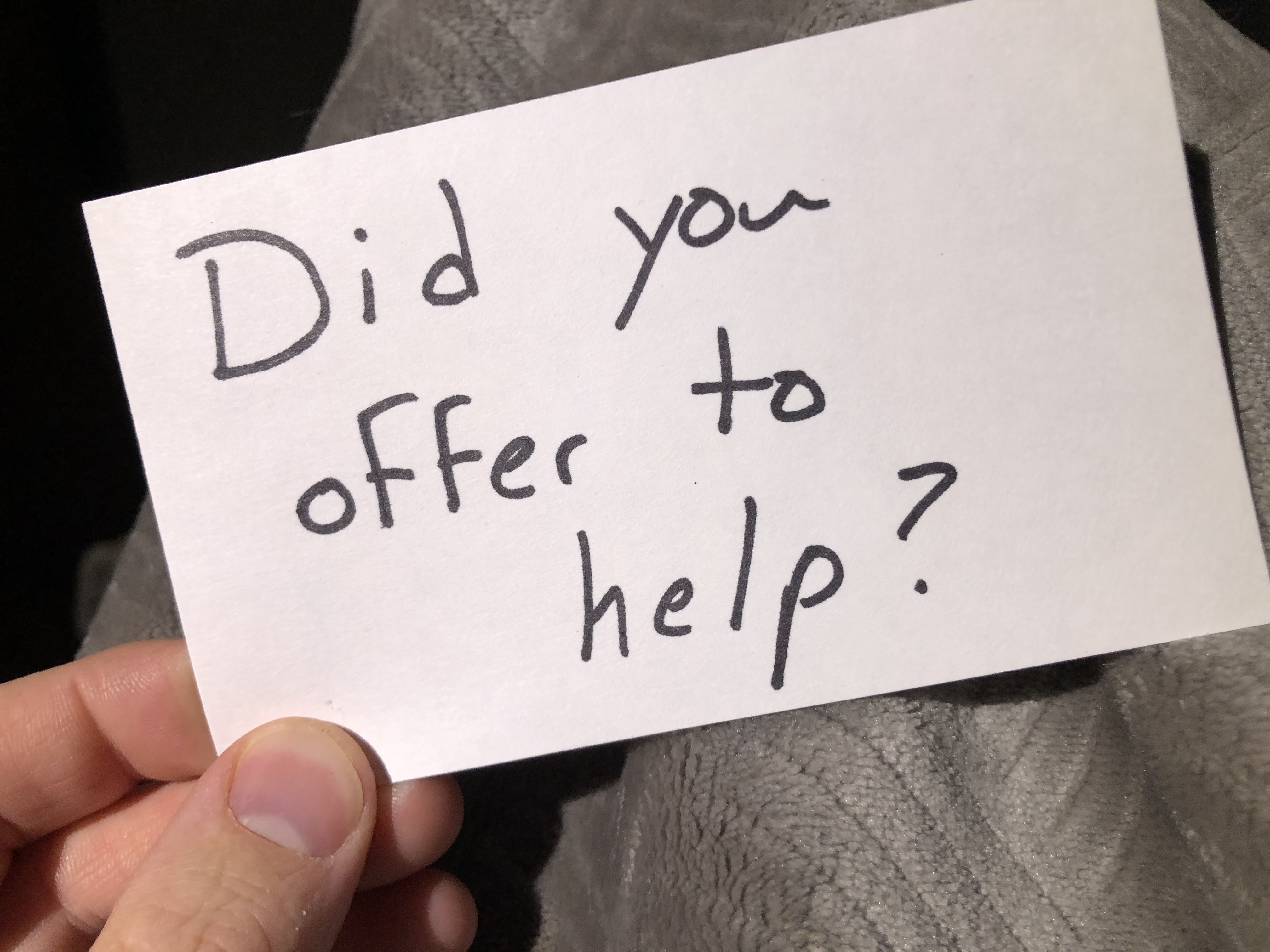

“Did you offer to help?” I replied.

“I told him he was doing it wrong, and he kept doing it even more wrong!”

“Did you offer to help?”

“No.”

“Next time, will you offer to help?”

“…yes…”

Now, thinking it over, I need that tattooed on the back of my eyelids. I need it as an out-of-office message. I need it in every moment I’m working with someone learning something new, and I need it in any conversation where an adult complains about a child.

If the answer is “yes,” then we are halfway there.

In What on Earth Have I Done? Robert Fulghum writes “I have more than enough. They do not. And here were are, face-to-face.” Fulghum’s words are in an essay tackling the moral and practical question of whether to give money to those asking for it in intersections and on street corners.

It comes down do, “Did you offer to help?”

It is not my job to judge them. It is my job to judge me.

Sure, if I give something to each and all of them, I may in the process give to someone who do not really deserve help. That’s the chance I take, but I will have not missed anyone whose need is real.”

– Robert Fulghum, What on Earth Have I Done?

Teachers will often talk about the real world and withholding assistance or the benefit of the doubt to students because such second chances will not be afforded students in the real world. Most of these conversations concern issues of great import in the fiefdoms of their classrooms. In the grand schemes of students’ lives, they are little, insignificant things. Late work, a missed citation, not showing how you got to your answer. The real world. Ugh. Even the IRS will give you an extension.

Our classrooms are the real world, certainly to the students compelled to be there each day. They are the laboratories of civic and social interactions, imparting implicit and explicit norms of what they should do when life’s training wheels are off. Withholding the offer of help and the benefit of the doubt models behavior our students will surely remember, and mimic, when they reach that mythical real world.

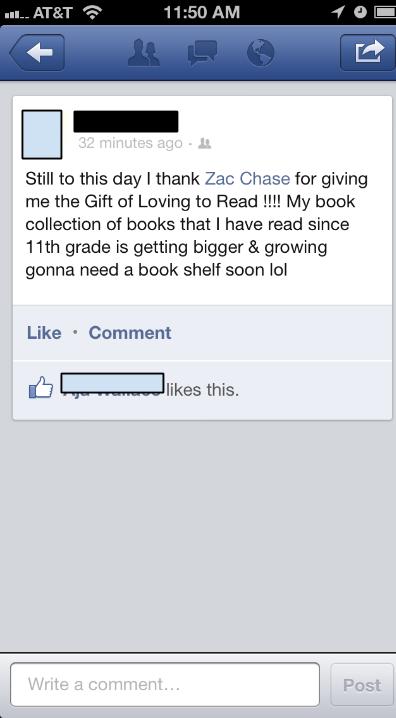

They will not remember the late homework assignment, but they will remember whether we helped when they asked.

What if we were to give to all whom ask? Yes, some will game the system, but that’s the system’s lot to contend with. Ours is to contend with who we’ve shown the world we are each day. Or, as teachers, what we’ve shown our students the world could be each day. “It’s my job to judge me.”

The photo below is of a card now taped to the lamp on my bedside table. I can think of few better questions of accountability to end my day with.