A colleague of mine is set to lead some professional learning for childcare workers. Her topic is trauma-informed care, and she reached out to see what I’d make sure to include if I were talking to the audience.

Not wanting to double up on what I was sure she’d already be sharing, I sent her the following from Fostering Resilient Learners by Kristin Van Marter Souers and Pete Hall:

I am going to introduce you to a powerful series of six communication steps to begin using with your students and loved ones. I use these often in the couples therapy work that I do, and I swear by them in my interventions in the classroom setting with educators, administrators, students, and families. The steps are as follows:

- Listen.

- Reassure.

- Validate.

- Respond.

- Repair.

- Resolve.

Souers points out we usually hit #s 1, 4, and 6 pretty well, and I’ll admit this used to be my classroom practice. When problems arose in my classroom or in adult classes I teach, these three steps felt like all I needed to “handle” the problem and move on. These three kept us on schedule.

Unfortunately, they didn’t live up to my commitment to care for those I was teaching. In truly frazzled moments, listening more likely ended up as hearing which led to responding in ways that were inauthentic and one-sided, which led to a resolution that took care of what I needed and maybe took care of a piece of what the other person needed.

Pretty decent fail on the ethic of care.

Luckily(?), Souers points out I wasn’t alone:

Repair is one of the biggest steps we miss in education. So often, we mistake a student’s return to regulation as a form of repair. But getting a student to a place of being able to return to the classroom does not constitute repair; it just means that the student may now be primed to reflect on what happened so that repair can actually take place. In addition, many of our students and staff have never had healthy repair modeled for them, so the concept is foreign. Many families engage in the pattern of rupture-separate-return, in which a disruption, argument, or hurtful exchange occurs; the parties involved separate from each other; and, after time passes, they return and act as though nothing happened. Opting not to address what occurred leaves a void of understanding and a lingering fear that the upset may happen again. We have a huge responsibility to model what healthy repair looks like and to incorporate structures into our discipline and corrective policies that enable this step to take place.

Souers, Kristin Van Marter ; Hall, Pete. Fostering Resilient Learners: Strategies for Creating a Trauma-Sensitive Classroom . ASCD. Kindle Edition.

Since I’ve started incorporating all six steps, I’ve seen a few key outcomes:

- I’m more connected to whomever I’m working with. The process is a mindful one. It requires me to stop what I’m doing and make sure I’m connecting with the other person.

- There’s more time. Whether working with my kids or with adults I may be teaching or managing, making sure we’ve worked through the entire process means the conversation isn’t lingering. In each 1-4-6 scenario, my day or time was often interrupted down the road because the other person hadn’t felt the repair and closure they needed to move on. Whatever the original problem, it would keep gnawing away at focus and relationships like an unattended to splinter. Now, we’re working things through, so they aren’t re-manifesting later on.

- I’m checkin in. As a somewhat conflict-avoidant person, I would often hit 1, 4, and 6 and then avoid the person and the problem for fear that festering splinter would start poking me. The issue, though, was always worrying me. As a caretaker, I remained concerned the other person was still upset and in need. A tough tension to navigate. Now, having worked through to repair and resolution, I feel much freer to check in with the person as a signal I’m still thinking about them and as a way to strengthen our relationship.

I’ve been thinking about the things I tell people about myself. I tell them I’m an educator, I tell them I’m a writer, I tell them I’m a vegetarian. I’m imagining, you do something similar. There are labels you carry with you and offer up to new people when you meet them. They might also be labels you count on as the fascia that binds you to your network of friends and colleagues. I wonder, though, if your labels are anything like mine.

I’ve been thinking about the things I tell people about myself. I tell them I’m an educator, I tell them I’m a writer, I tell them I’m a vegetarian. I’m imagining, you do something similar. There are labels you carry with you and offer up to new people when you meet them. They might also be labels you count on as the fascia that binds you to your network of friends and colleagues. I wonder, though, if your labels are anything like mine.

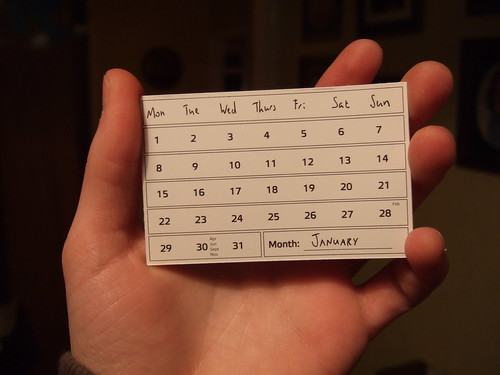

In exactly one month, Chris and my book

In exactly one month, Chris and my book