30: Which conversations are you sustaining and which are you letting go of? #LifeWideLearning16 @MrChase

— Ben Wilkoff (@bhwilkoff) January 30, 2016

As of June 15, my contract on my day gig will be up, and I’ll need to find some other way to keep my dog fed. As much as I’ve been thinking about geography when grappling with what this change means, I’ve been thinking about what kinds of conversations I want to be in and which ones I want to leave behind. With five and a half months left on the calendar, I’m gaining clarity.

The conversations I most want to sustain and move forward are those around equity and purpose. The first means all equities. I want to talk about the kid in middle school who realizes he’s gay and can’t access educational and social experiences like teachers’ use of heteronormative language and not feeling comfortable asking his crush to the school dance. I want to talk about the fact that if most school leaders say they invited their honors or gifted and talented-labeled students to participate in a program then I can be almost certain they didn’t invite students of color. I want to talk about how students in rural schools don’t have the access to arts, cultural institutions, and educational opportunities their urban- and suburban-dwelling peers have every day. As many flavors of equity as we can bring to the table, that’s what I want.

In all of my grad school experiences, I have asked and searched for an answer to the same question to no avail, “What is the pedagogy and practice that drives this institution of learning?” Silence each time. I ask a similar question of principals and superintendents, “What are the three things we are working toward this year?” Silence (usually uncomfortable), and then a garbled answer.

Thus, I want to improve conversations of purpose. For any action, program, or scheme; I want to help make sure there’s an answer to “Why are we doing this?” Similarly, for all askings of “What are we going to do?” I want to help organizations and people look to their agreed upon purpose for helpful guidance. If you don’t know your mission statement, then it’s probably not your mission.

The conversations I’m willing to step away from are simple. Anything that starts with, “How can technology…” Technology should not drive the question. It should be considered as an answer to a possible problem, and it becomes boring to be in room after room and seen as a person who is there to bring up technology before he brings up people and relationships. In the conversations I’m seeking, I hope to enter fewer rooms with that presumed persona in the same way a master carpenter probably doesn’t want to be “that lady who loves talking about saws.”

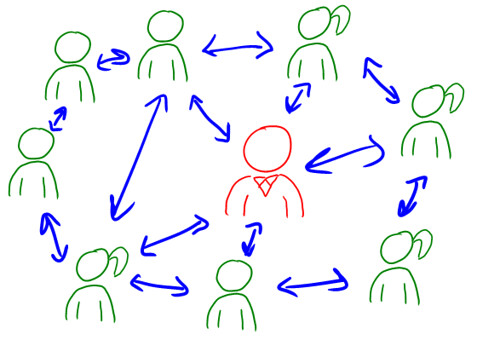

This post is part of a daily conversation between Ben Wilkoff and me. Each day Ben and I post a question to each other and then respond to one another. You can follow the questions and respond via Twitter at #LifeWideLearning16.