I teach kids.

First and foremost, I teach kids.

It’s always in the front of my brain.

The stupendously great thing is I get to teach kids something I love.

In the important rhetoric around the idea that I teach kids, I want to make it clear that I teach kids a subject or a discipline or a an art.

Sometimes, it’s all three.

My only real run-in with diagramming sentences was in Dr. Jerry Balls’s Traditional and Non-Traditional Grammar course in college.

For most of the other students in the room, diagramming sentences was the hellacious experience I remember it being portrayed as in some episode of The Wonder Years.

For me, though, something else was there. In diagrams, I saw something beautiful. The way Mr. Curry had seen beauty as we worked through problems in calculus or Mr. Schutzenhoffer saw beauty in the molecular models of chemistry, I was seeing tangibly represented in the subject I identified most closely.

I wanted to talk about what I saw, the way what language was doing was being played out in what we were seeing.

Dr. Balls and my classmates wanted to finish the lesson.

He was teaching a subject.

The seniors in my storytelling class started today at SixWordStories.net.

“Read until you’re moved to create,” I said, “Then let me know when you need a marker.”

They started reading.

Around the room, I heard students reading key stories aloud.

Not surprisingly, the sexy stories were a pretty big hit.

Gradually, hands went up.

I took them markers.

“What do I do?”

“Write some six-word stories.”

And they started to write stories on their desktops – all over their desktops.

Missy covered her entire table and had to move to another to keep writing.

At some point, when the tables of the room were awash with stories – beautiful, heartbreaking, hilarious stories – we watched a simple video I found as I was digging around the TALONS English wiki.

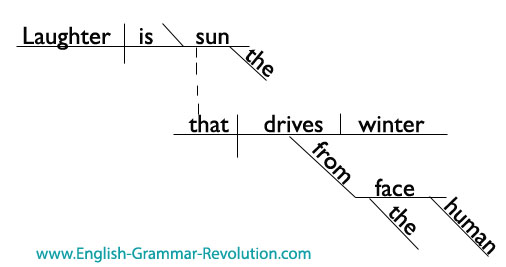

The video ended. “For the next step, you’ll be diagramming your stories. I can tell by the somewhat terrified looks on many of your faces that you haven’t the foggiest idea how to diagram a sentence. That’s ok. The Interwebs has millions of pages to help you out.”

A beat.

They began looking up the information they needed.

A few minutes later, they were taking their works of literary art and deconstructing them. We started to talk about how where the words were related to what the words were and how the story did or didn’t change when all the same words were in a space together but being asked to show how they were doing what they were doing.

Tomorrow, we’ll head to the final phase.

We’ll move our diagrammed stories (and I say our because I’m writing one as well) off of the tables and onto tangible objects and representations to be displayed around school. The subject of storytelling, the discipline of diagramming and the art of creation will be knotted together.

When students ask me why I chose English, I explain I love words. I love their power, their beauty, their arbitrary natures, their shifting meanings.

I know few, if any, of my students will major in English as they further their studies. I’m perfectly happy with that, so long as they can see English.

As much as I would not be doing my job if I didn’t work every moment to see my students, I would also be failing if I didn’t work to help them to see the transcendent beauty of my subject – to try on a new perspective.

Very nice — using diagramming as a means of analysis. I love diagramming but, I'll admit that I've never taught it.

Sentence Diagramming! (A chorus of young TALONS simultaneously groans and cheers the prospect of others undertaking this most onerous of rhetorical undertakings…) We had some fun this year taking apart the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (as it sounds, the Canadian equivalent to the American Bill of Rights / Constitution), and diagramming them in small groups, which turned into discussion around the role language plays in law, democracy, and in setting out our inalienable rights and freedoms. In diagramming, it becomes pretty clear pretty quickly whether or not a sentence or phrase has been constructed correctly – or elegantly – by how the structure takes shape. Embedded in the debate about where a prepositional phrase is attached to a main clause is discussion, and appraisal of a word's (or words') power, and their shifting, subtle uses. It may not be all that popular – some of our kids get revved up at the thought of something in English class that is objective (where there is (more or less) a “right answer”), and this sort of analytically challenging exercise; but many groan, struggle, and are not, admittedly, huge fans of the stuff – but is damn powerful stuff to get into. An all too-often neglected piece of the study of English, for sure, for which I am indebted to a particular stickler of an English prof at the University of Arkansas, who showed me the way of sentence diagramming, Chomskian Trees, and some other stuff that I thought belonged in a science course, but gave me a much greater understanding of the way our living language works. Even though I might have groaned about it at the time. (Can you blame me? He's a guy who wrote this: http://ualr.edu/epmoore/crseva…) Personal sentence diagramming favourite: http://www.slate.com/id/220131…/Looking forward to the six word stories, diagrammed!

I love you.

My first real experience with sentence diagramming was also an English grammar course in college. It was taught by this amazing and infections Romanian woman. I became mesmerized by the whole process, as if I'd finally found a way to unite my two loves of algebra and language. It's very mathematic and I find that fulfilling. (Off to diagram the sentences in this comment…)