The Gist:

- My G11 students are reading The Great Gatsby.

- After the choice afforded them in the last quarter, I can’t be every other English teacher.

- We’re challenging the Academy and having numerous books vie for the title of Great American Novel.

The Whole Story:

Monday, I tweeted out the link to a simple questionnaire. It contains two statements: 1) What is the Great American Novel? 2) If you’d like to make your case, do it below.

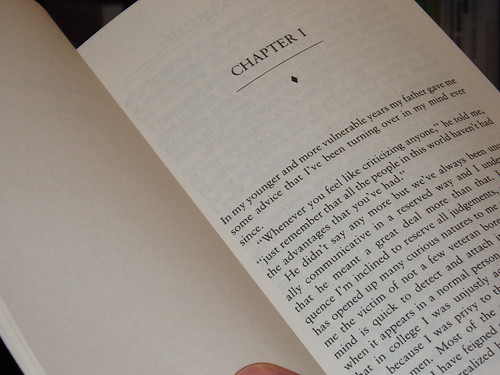

My G11 students also received their copies of our latest class novel Monday. Maybe you’ve heard of a little book called The Great Gatsby? Apparently, it’s quite popular. In fact, many argue it qualifies as the GAN.

Narrowing down the results of the questionnaire, my classes will be pitting 8 contenders against one another. The final contender will face off against Gatsby.

I’ve written about this before. The original idea was to put Gatsby on trial for libel and slander against other novels. After consulting with many people whose thoughtfulness and opinions I greatly value, I was left with a sort of literary March Madness.

I won’t be walking my students through Gatsby. I won’t be indoctrinating them to the symbolism of that light at the end of that dock. I won’t be talking about the American dream or gender roles and the power of adhering to them.

Instead, I’ve given my students some simple instructions:

Read this book with the idea that you will either have to argue against its status as the GAN

or defend its standing as the GAN.

If the American dream and gender roles and symbolism are really key and keen in the text, they should pick up on them. If something else is there, they’ll pick up on that. Is the symbolism important because my teachers told me it was there or because it’s important? I want to start clean.

We’ve talked about some strategies for tracking their thinking. They can use the tried and true sticky notes. They can make a bookmark for each chapter where they track positives on one side and negatives on the other. They can take notes in a notebook. Turns out I don’t care.

They’ve until April 5 to finish.

During classes, they’ll frequently have time to read, about 20 minutes. Tomorrow, I’ll help them decide how to schedule their reading. They’ve 180 pages of 9 chapters and either 12 or 7 days depending on if they want to read over Spring Break. Their pace and rate are up to them.

During the remaining 2/3 of class, we’ll be debating and deciding the qualifiers of the GAN as well as practicing discreet reading and writing skills using other texts.

April 5, they’ll compile their notes, hand in their copies of Gatsby and find out which text they’ll be reading over the next two weeks. This will, be the text on whose behalf they’ll be arguing.

Rather than discussing qualifiers of the GAN, we’ll be using non-reading class time to examine literary lenses they can use to make their cases – Feminist, Marxist, Reader-Response, Postcolonial, Deconstructionist, New Criticism. Throw in some more discreet skills, and you’ve got a hopping time.

The results coming in on the questionnaire are backing my decision to head this direction with things. Largely, the texts suggested line up as canonical standards. It seems dead white guys were really in touch with how to write in a way that resonated with the American spirit.

My goal for this is not to have my students look at any of these texts as the GAN, but to look at these texts and ask why they hold the status they hold and then ask whether or not they deserve that status.

I’m curious to see what they think.

You’re probably asking, “Wow, Zac, that’s great. But, what can I do to help?”

Great question, you.

If you haven’t already, take about 2 minutes to complete the questionnaire and nominate your contender for GAN.

Starting Friday, we’ll be seeding the top 8, check back then to help fill out our brackets.

Oh, one other thing, talk about your nominee with someone. The conversations I’ve had in the last two days have definitely enriched my appreciation for literature. If nothing else, twitter’s seemed less monocultural for a day or two.

Here are the standings:

Here are the standings: